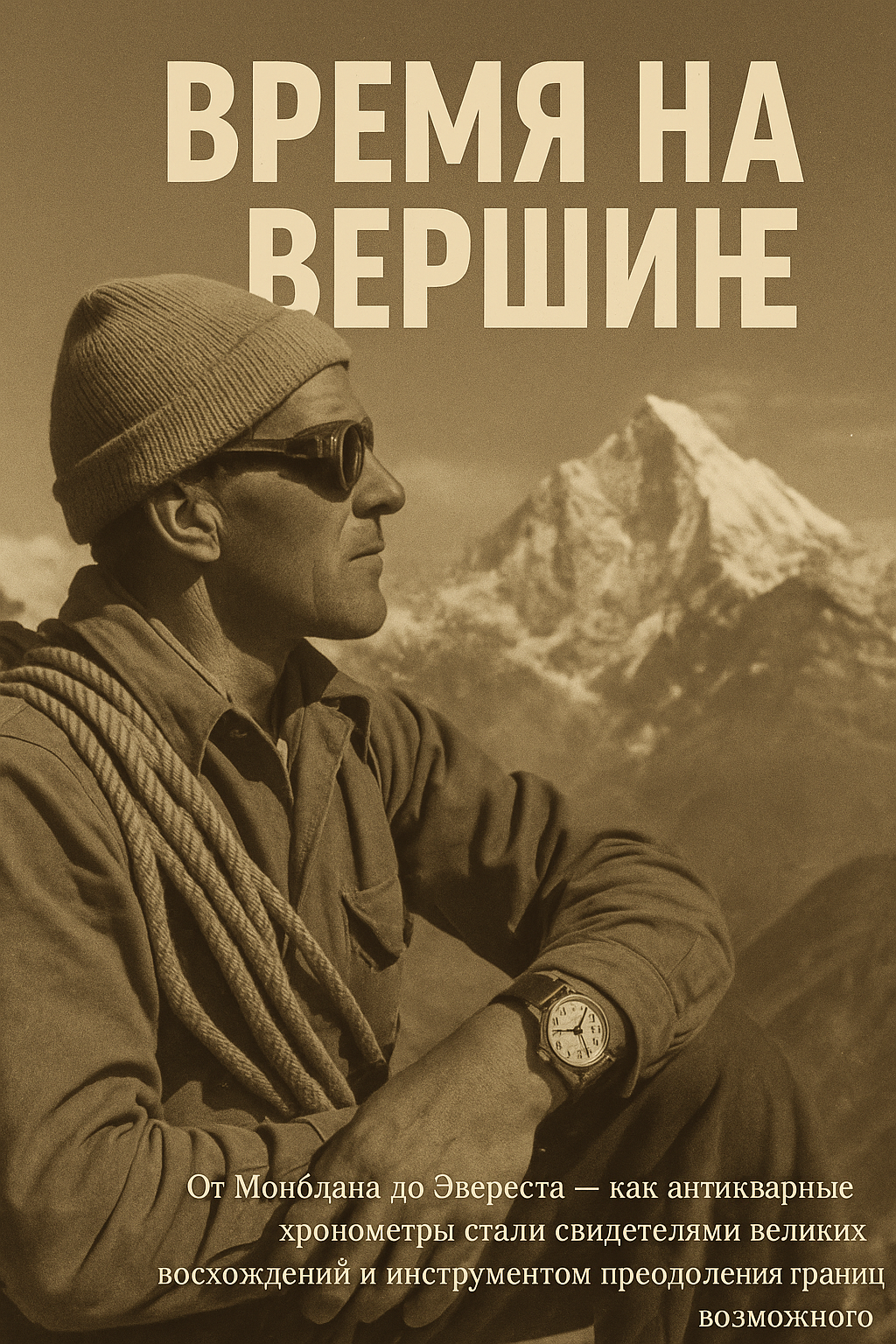

How human will and the precision of Swiss watchmaking changed the concept of time and altitude.

Time that conquered Everest: how mechanical watches witnessed the triumph of Hillary and Norgay, the first climbers to reach the top of the world.

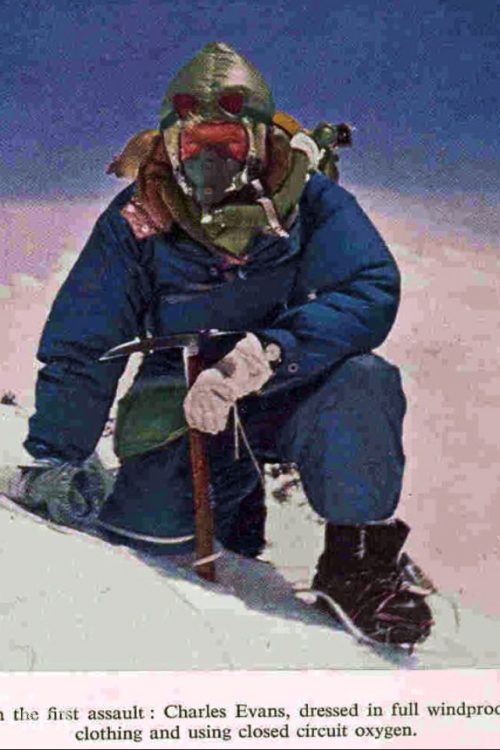

On May 29, 1953, at 11:30 a.m., man became the first person in history to reach the summit of Everest. Sir Edmund Hillary and Sherpa Tenzing Norgay reached 8,848 metres, the point where oxygen becomes scarce and metal freezes to the point of brittleness. Along with them, two silent expedition members also conquered the summit: a mechanical watch, a Smiths De Luxe and a Rolex Oyster Perpetual.

Two brands, one ascent

Tested by Time and Cold

Temperatures on the final stretch of the climb dropped below -30°C. The oil in the mechanisms thickened, the metal contracted, and the glass threatened to shatter from the extreme pressure drop due to the altitude. Yet both clocks withstood these trials. When Hillary and Norgay took a photo together at the summit, their watches continued to tick—symbolizing the inexorable passage of time even where everything around them stood still.

After the Ascent – A Dispute about the First

After returning home, Hillary publicly thanked the Smiths company, uttering the now legendary phrase:

“I carried your watch to the summit. It worked perfectly.”

“The first to conquer Everest.”

Thus began one of the most famous rivalries in watchmaking history – the debate over which watch “reached” the top of the world.

A mechanism that became a legend

Today, both the Smiths De Luxe and the 1953 Rolex Oyster Perpetual are considered historical relics. They remind us not only of the conquest of Everest, but also of a time when mechanical precision was measured by human courage.

Collectors call such watches “witnesses of altitude” – artifacts that bear the marks of extreme conditions, but continue to run after decades.

Fact 1. Two brands of watches were used during the 1953 expedition

On the conquest of Everest, Sir

-

Smiths De Luxe — British-made, officially provided by the expedition.

-

Rolex Oyster Perpetual is a Swiss watch provided by Rolex as a sponsorship piece.

Fact 2. The Smiths De Luxe watch was the official choice of the British expedition

Expedition leader John Hunt and the British sponsors wanted to emphasize British engineering independence. Therefore, the official watch The expedition‘s watches were specifically Smiths De Luxe, made in England, and not Swiss Rolex.

The official 1953 report states:

“All members of the expedition were equipped with Smiths watches — made in England.”

Fact 3. Hillary himself actually He carried Smiths to the summit.

After returning from Everest, Hillary publicly thanked Smiths, famously saying:

“I carried your watch to the summit. It worked perfectly.”

This quote was published in British newspapers and used by Smiths in advertising in the 1950s.

Thus, Hillary was wearing a Smiths De Luxe watch at the summit of Everest, not a Rolex.

Fact 4. What happened to Rolex?

Rolex also provided several Oyster Perpetual watches to the expedition members. Tenzing Norgay actually wore one of them (some sources say he had both a Smiths and a Rolex).

After the expedition, Rolex actively exploited the event in advertising, claiming that their watches had also reached the top of the world—which is technically true, as there were members of the team wearing Rolexes. However, this was a marketing ploy, not a documented fact regarding Hillary personally.

Fact 5. The Fate of That Very Watch

-

Hillary’s Smiths De Luxe watch is now believed lost or held in a private collection, presumably in New Zealand.

-

One of the Rolex Oyster Perpetual 1953 watches from the same expedition is in the Rolex Museum in Geneva.

Epilogue

Everest in 1953 was not just a geographical peak, but the pinnacle of human excellence—in both mountaineering and watchmaking.

The Mechanics of Altitude: Breguet, Mont Blanc, and the Birth of Scientific Time

August 8, 1786Doctor Michel-Gabriel Paccard and guide Jacques Balmat reached the summit of Mont Blanc (4808 meters above sea level).

Their ascent, which lasted almost 14 hours, was not only a geographical feat, but also a scientific experiment. They carried not flags in their backpacks, but scientific chronometers by Breguet and Berthoud, barometers, and thermometers—instruments designed to prove that altitude can be measured in time.

Watches as a Scientific Instrument

The end of the 18th century was an era when time became the basis of the exact sciences. The chronometers of Abraham-Louis Breguet and Ferdinand Berthoud were considered the most accurate in the world: their error did not exceed one second per day. These watches were used by sailors, astronomers, and surveyors—and in 1786, mountain climbers also used them for the first time.

Paccard, a physician from Chamonix, sought not fame but scientific proof. His goal was to measure the barometric pressure and temperature at the summit and, using a precise clock, record the dynamics of these readings over time. His notes contain a phrase that has become the quintessential expression of the Age of Enlightenment:

“Time is the key to heights. Without precise time, no science will rise above the valley.”

Ascent in Time

At 4 a.m., according to the Berthoud watch, Balmat and Paccard began their ascent from the Bossons Glacier. Every half hour they checked the barometer, temperature, and the position of the sun.

At the summit, around 6:30 p.m., the Breguet watch showed 14 hours 27 minutes of active movement. It was this data that later formed the basis for the first calculations of Mont Blanc’s height using Laplace’s formulas—the first-ever precise scientific determination of the mountain’s height.

Breguet and the Birth of Precise Time

The ascent of Mont Blanc in 1786 was a turning point not only for mountaineering but also for watchmaking. Just a few years later, Abraham-Louis Breguet introduced his legendary tourbillon pocket watch (1801)—a mechanism that compensates for the effects of gravity on precision.

It is believed that the experience of mountain climbers and physicists at altitude inspired Breguet to make this discovery—an attempt to harness what is most strongly felt in the mountains: time, which flows differently.

Mont Blanc as a Laboratory

Following the success of Paccard and Balmat, scientists set out for Mont Blanc. As early as 1787, Jean-Baptiste Delambre and Horace-Bénédict de Saussure repeated the ascent, carrying improved Breguet watches with a double balance and more stable escapements. Their records formed the basis for the first altimeters and the concept of “altitude time”—the dependence of atmospheric pressure and temperature on the behavior of a watch mechanism in thin air.

In 1815, King Louis XVIII of France learned of the outstanding performance of Abraham-Louis Breguet’s marine chronometers and appointed him timekeeper of the French Royal Navy. From that moment on, the success of royal expeditions began to depend largely on the reliability of marine Breguet’s watches, which entailed both great fame and enormous responsibility.

The term “marine chronometer” applies to all precision watches designed to meet the requirements of the French Navy for military or commercial purposes. Marine chronometers are rather large, cylindrical brass objects with large movements inside. The chronometer case is attached to a sturdy wooden box, usually mahogany, by a brass gimbal, which serves as a stabilizer and shock absorber. A marine chronometer with carrying handles and a glass cover for reading was placed in the sanctum of the ship, the captain’s cabin, and was considered one of the most valuable instruments on board; among other things, it was used to calculate longitude during a voyage. According to Breguet’s own notes, he worked on marine chronometers from the very beginning of his career and was always obsessed with improving their accuracy and contributing to the legacy of famous watchmakers. masters of the past from Britain and France. However, Breguet only began to produce “naval watches” en masse after his appointment as Supplier of Chronometers to the Royal Navy in 1815. His devices, equipped with one or two barrels, usually had an easily removable chronometer escapement (detent), which greatly facilitated their repair and maintenance.

Epilogue: Time That Ages Not

Today, antique Breguet and Berthoud watches from the late 18th century are kept in museums in Paris, Geneva, and La Chaux-de-Fonds. Their hands have long since stopped, but the story continues. Mont Blanc has become more than just a symbol Mountaineering – it became the birthplace of scientific time, time measured by human courage and mechanical precision.

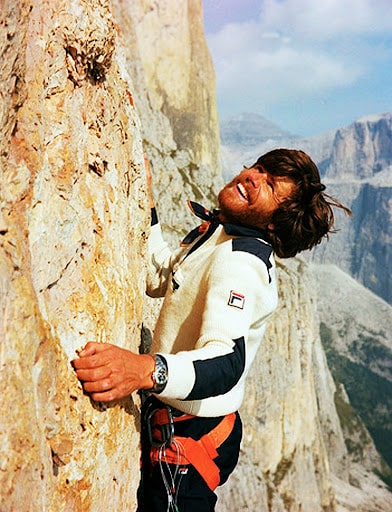

Time without oxygen: Reinhold Messner, Everest 1978, and the Rolex Oysterquartz Datejust

On May 8, 1978, at 1:15 PM Nepal time, two men stood on top of the world. Reinhold Messner and Peter Habeler became the first to climb Everest without oxygen, achieving what was considered impossible.

Messner wore a steel Rolex Oysterquartz Datejust watch on his wrist during the climb, a world-famous symbol of practicality and precision.

When the air runs out, but time remains

By that time, Messner was already a mountaineering legend. His style ascents – easy, fast, without unnecessary equipment – contradicted the traditional”siege” tactics of all Himalayan expeditions.

In 1978, Messner decided to take a step that experts called suicide – to climb Everest without oxygen tanks.

In conditions where the pressure drops to a third of the Earth’s, and the blood loses oxygen saturation, even simple actions at such an altitude become extremely difficult, one might say, on par with a feat. And if you also refuse oxygen tanks, the chances of a successful ascent and descent are practically zero.

The Rolex Oysterquartz Datejust – a tool, not a decoration

The Oysterquartz Datejust Ref. 17000, released in 1977, was a technical revolution. The quartz caliber 5035 combined an accuracy of ±1 second per day with a classic Oyster case—hermetic, frost-resistant, vibration-resistant, and resistant to pressure changes.

This combination made the watch an ideal companion in extreme conditions, where mechanical movements often froze due to thickening oil.

Messner, a pragmatist and perfectionist, chose not a symbol, but a reliable instrument. Quartz was unaffected by temperature fluctuations and required no winding. At altitude, where every breath is a struggle, such reliability became a matter of survival.

Everest as the Limit of Possibility

Messner and Habeler left camp at 8,300 meters at two in the morning. The temperature dropped to -40 °C. The wind tore at the tents, and their breath turned into ice crystals.

They reached the summit by midday. Messner recalled:

“I stood where breathing has no meaning. Where the body screams ‘no,’ and the mind says ‘yes.'”

At the moment he raised his head and looked at the horizon, his watch continued to tick. The cold could not stop either the quartz pulse or the man driven by an internal rhythm.

Rolex and the Philosophy of Silence

When Messner descended, Rolex representatives commemorated his achievement with a modest line in the press release:

“Rolex congratulates Reinhold Messner and Peter Habeler — who have redefined the limits of human endurance.”

The company didn’t advertise heavily or release limited editions. But the story has gone down in the brand’s annals as proof of its precision and reliability.

Epilogue: When Time Breathes With Man

Today, the original Rolex Oysterquartz Datejust watch with which Messner conquered Everest is kept in his private collection in South Tyrol. Its case is worn, the crystal is slightly clouded with age, but the hands still move.

Messner said:

“Time in the mountains is the only thing you can’t fool. It either goes on or it ends.”

These words became the philosophy of an entire generation of climbers.

And perhaps this is the true meaning of that ascent: a man left without air, but not without time.

Navigation above Clouds: Omega Speedmaster and the First Ascent of Cho Oyu in 1954

On October 19, 1954, a Swiss expedition led by Herbert Tichy, together with Josef Jochler and Sherpa Pasang Dawa Lama, reached the summit of Cho Oyu (8188 m) — the sixth-highest mountain on the planet. This was the third ascent of an eight-thousander in history and the first, Completed in “Alpine style”—without heavy camps and with minimal equipment.

Among the few items the climbers took with them were an Omega Speedmaster watch, which became an integral part of this expedition and a symbol of a new generation of “high-mountain watches,” or watches for altitude and extreme conditions.

Omega – precision born in Switzerland

B In the early 1950s, Omega collaborated extensively with Swiss mountaineers, providing them with chronographs designed for extreme temperatures and low pressure. The prototype of the future Speedmaster, released in 1953, already featured a stopwatch function, a tachymeter scale, and a reinforced antimagnetic case—qualities that made it an ideal companion for high altitude.

When Tichy was preparing his expedition to Cho Oyu, Omega provided him with several examples of its chronometers for field testing. Among them was the very device that would later become known as the “Speedmaster before Speedmaster”—the model that had endured glaciers and altitude before reaching “Space.”

Time as a Landmark

The expedition set off from the Tibetan side on October 5, 1954. Weather windows were short, visibility often dropped to zero, and altitude sickness threatened every participant. In conditions where maps and compasses were not always helpful, watches became a navigational tool: Tikhy used time to calculate the length of passages between ice ridges, and he used changes in the mechanism’s movement to estimate temperature differences and possible changes in atmospheric pressure.

In his diary, he wrote:

“When the horizon disappeared, time became my only direction. If the hand moves, it means we are alive and moving forward.”

These lines were later quoted by Omega engineers, claiming that it was Tichy’s spirit that inspired them to create the Speedmaster philosophy—”a watch for those who go beyond the horizon.”

Altitude Test

At an altitude above 7,500 meters, the temperature dropped to -35 °C. The lubricant in the mechanisms thickened, but the watches continued to run. During the descent to base camp, the participants checked the accuracy – the deviation was just four seconds over twelve daysin conditions where not every person could survive, the mechanics performed miraculouslyA forest of endurance and precision.

When the expedition returned to Kathmandu, Omega representatives officially documented this result. From that moment on, the brand became associated not only with marine and aviation instruments, but also with mountaineering.

From the Himalayas to the Stars

Five years after Cho Oyu, in 1959, Omega released the production Speedmaster model, based on the Himalayan trials. The same design, tested by Tichy at altitude, would later be worn by Neil Armstrong on the moon in 1969.

Epilogue: When Time Becomes a Direction

Today, the original Omega watch used during the ascent of Cho Oyu is kept in the archives of the museum in Biel, near the company’s factory. The case back is engraved: “Cho Oyu Expedition 1954”.

They remind us that sometimes mechanics can be the guiding thread in the chaos of the elements—and that time, when measured correctly, can lead a person even out of the clouds.

Source of the article: alp.org.ua