Each mountain is a separate living organism: with its own soul, history, and peculiarities (sometimes strange) in structure and behavior. After two successful expeditions, I finally recognized the territory of sympathy for me on the part of perhaps the most iconic object in the Caucasus: Ushba.

Carefully studying the history of successful ascents of this Beauty, two general trends can be traced: it was successfully climbed either by carefully planned, precisely calculated, and very powerfully equipped “battering rams” in the form of championship teams – but this was in the USSR, with its All-Union Central Council of Trade Unions funding, command-and-control system, and human resources in the “if you chop down a forest, the chips fly” format. The second tactic is expressed by the now-fashionable phrase “Fast & Light.” During Soviet times, the lion’s share of such attempts ended fatally, earning Ushba a place on the world’s sad list of man-eating mountains. There were, of course, some successful blitzes, mostly on various more or less certain classic routes. However, the Mountain’s prices are far from humane: according to various sources, between 50 and 70 missing people lie unaccounted for in Ushba’s inaccessible rocky gorges and glaciers.

In the early 1990s, everything necessary for climbing such peaks finally became available for sale. A new wave of well-equipped and wealthy climbers swept up Ushba’s walls and ridges, but… Experience has shown that good gear helps, but it doesn’t solve the mountain’s primary problem. It turned out that the level of rock and ice climbing, physical fitness, and efficient and competent handling of equipment are not for sale in mountaineering stores. The new European style of “show-off” climbing, superimposed on the residual Soviet school (though it had many positive aspects), once again yielded a harvest of sadness and grief.

In short, there was much to frown upon. An analysis of accidents showed that 90% of them were due to Ushba’s very specific climate: bad weather arrives suddenly, and is distinguished (compared to the surrounding mountains) by its ferocity – according to those who have endured it, “…the wind is stronger, it’s colder, and the snow is somehow prickly…” In 20-30 minutes, it can all end as suddenly as it began – with sunshine and clear skies again. Or it can drag on for two or three days, with periods of worsening conditions. Considering the scale of the object—this isn’t Pakistan or the Himalayas, after all—the siege tactics seem somewhat incongruous. But what would those who never returned say about this? So there!

However, “…experience is the son of difficult mistakes, and genius is the friend of paradoxes!”

On August 1st, 2004, in alpine style and without acclimatization warm-ups, I led a “teapot” to the summit of Northern Ushba at 8:00 PM. This happened on the fourth day after leaving the “Shkhelda” AUSSB. On the third day, we were frankly fooling around on the Ushba plateau after the morning climb from the German bivouacs. We descended at night along the ascent route, however, leaving six rappel ice screws behind in the “Board.” And for all five days and nights, including the day of departure, the weather was perfect.

This time, the plan was far from 4a, and the gang seemed to be no strangers. In any case, when I asked, “Are you running?” I heard, “Yes, sir!” And when I asked, “Is everything alright with your fixed ropes?” they answered, “Even better than you can imagine, boss!” There’s no time to check, you know—work, work.

This time, the plan was to re-climb the Monogarov Line on the “Pillar” of South Ushba. Considering the route’s age—it’s 45 years old and pointless by today’s standards (it’s a 350-meter bolted route), the idea was to climb along it, but our way: maximum freeclimbing, and if aid climbing, a minimum of retained gear, but 100% reliable. There was no information about the site other than looking at photos and the rather sparse information from Mr. Chaplinsky (“…you can take a lick, Mr. Mikhail, banzai!”), which entailed 20 (!) kg of gear – everything and a lot, except for the removable bolts. The climate, too – see above – determined the need for a good base under the “Pillar.”

Arriving – they arrived, arriving – they arrived, bringing – they brought. It seemed fine, admittedly in the rain, but for the better – it wasn’t so hot. But after the first climb up the approach ridge (it turned out to be not as easy and short as it seemed), the two helpers shook their heads: “It’s hard, it’s scary! We’re tired, we can’t do it!” When asked about physical training, the answer was silence. In short, they dropped off, and not only that – away from the mountain in an unknown direction and for an indefinite period. The second pair helped as best they could, and also realized they were somewhat unprepared for this, but remained vigilant and in touch. From there, from the middle of the ridge to the “Pillar,” two days of back-and-forth work were required.

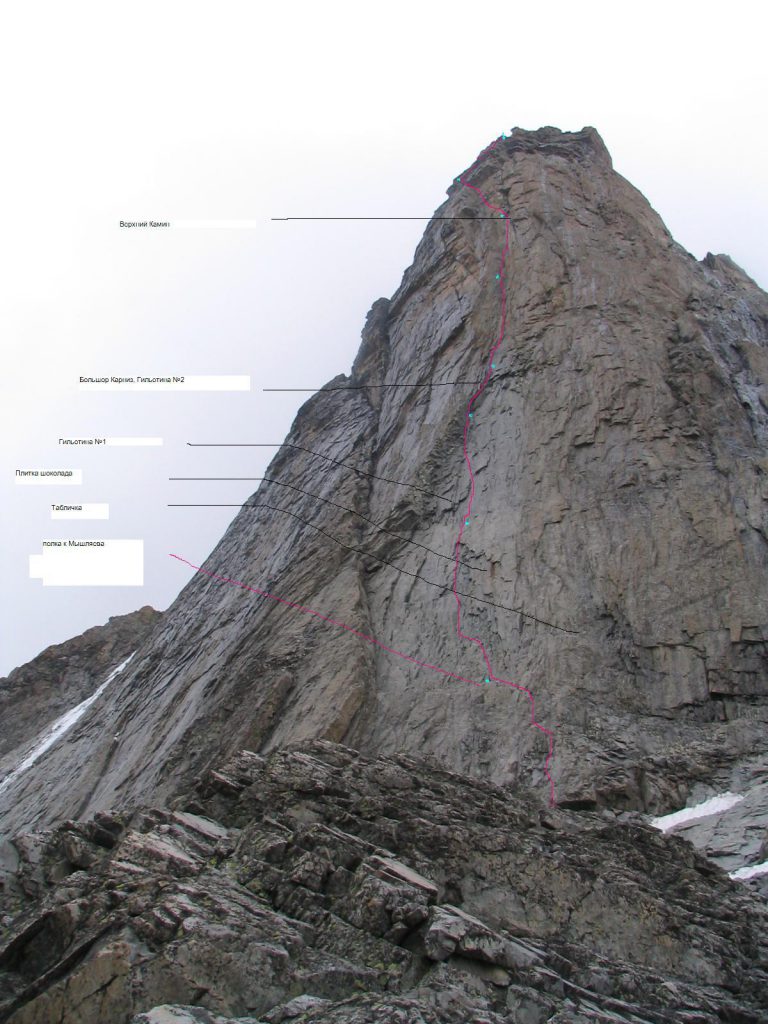

Well, now the fun begins. Having found and examined Vladimir Dmitrievich’s line, I realized that, if successfully executed, the plan would be met with less-than-flattering criticism.The direttissima, traced with a ruler in the photo, has simply been transferred to the rocky outcrop. There’s no logic or connection to the terrain by definition. But no problem—the corridor to the left is about 60 meters to Myshlyaev, quite glamorous and creative. The subsequent events are described in dry, technical terms at the beginning (…see to the top of “Stolb”). We spent five days on this: Five days to Verkhniy Kamin, on the sixth day we picked up supplies at the base of the approach ridge, on the seventh day we reached Myshlyaev Route to the left, around the corner, and on the descent we encountered heavy rain and snow. On the eighth day, we decided to rest and dry out, and considered moving our camp to the top of “Stolb.” Even leaving all the essentials, our backpack weighed 13-15 kg. We’ll try again tomorrow.

All early morning attempts were unsuccessful – neither jumaring with a backpack suspended beneath us, nor the idea of pulling it along: at least one human power was lacking. Two people could accomplish this task, but only if we’re talking about 100-150 meters of wall. Here, it’s almost 400 meters, perhaps even more. We spent the rest of the day eating and sleeping.

On August 6th, we were already up and about by 3:00 AM, and by 4:00 AM, the jumars were rustling along the fixed ropes. Along the way, we prepared a retreat route in the form of ultra-reliable stations, almost vertically, one below the other, and spaced 55-57 meters apart: so as not to miss even in pitch darkness. The 120m climb from the bend to the top of Stolbo turned out to be challenging and required exceptionally careful climbing – everything was thawed, and there were a lot of loose rocks. Then the Big Wall ended, and alpine climbing began, with ice, easy rocks, snow, and other delights of the alpine terrain. In the middle of Krasny Ugol, snow and wind started blowing, and I finished it (thankfully, no higher than 5c+ – 5c) climbing very carefully, clearing every hold. We practically raced up the final ridge of Krysha, and at 7:40 PM Kyiv time, we were on the icy ridge of the summit!

Before complete darkness, we managed to rappel to the base of Krasny Ugol, where we safely spent the cold night.

The next morning, the footage reversed itself – and we were back home, under Stolbo. The next morning, we packed up and set off. Halfway to Zelenka, the weather turned nasty, and we suddenly felt an indescribable fatigue, so we didn’t want to do anything anymore. But, as agreed, our observers arrived to help, and we began to stroll joyfully through the vast expanses. I just had no energy left for singing.

So, about Ushba’s favoritism for me. First, it doesn’t want to see me on its peaks before 7:30 PM. Second, with a partner who’s incompetent in mountaineering. Third, it really enjoys tormenting me about my left knee. But in both cases—the first for 5 days, the second for 12 (!) days—it provided exceptional weather.

These, boys and girls, are the peculiarities of Ushba that have haunted me for the last six years. Mysterious? Perhaps, but there’s no need to systematize it.

With Love

MISHEL

Route Description:

A little logistics:

From Kyiv to Kutaisi – Boeing 737, then through Samstredia and Zugdidi to Becho, where we turned off for Mazeri (all of this is a Ford Transit). We stayed in Mazeri from 5:00 AM to 3:00 PM waiting out the rain, after which we quickly repacked and arrived in “Zelenka” under the Ushba Glacier in the dark. Then there were two days of shuttle transport to the glacier below the Mountain. The next day, the Doctor and I loaded up, reached the drop-off point, and over the next two days, hauled all the gear under the “Pillar,” the crux of the route.

Well, then there were five days of first ascent, a day of rest, a day of climbing Vladimir Dmitrievich’s bolt path (or rather, what was left of it), and then we descended to the start of the ascent.One ridge behind the supply from Skubak and Vasiliev.

Then there was an attempt to move the camp under the “Pillar” to its summit (failed due to the lack of at least one more person), and we rested for the rest of the day. And finally, a successful blitz to the Summit, rewarded with a cold night’s sleep.

The return trip was in reverse order, only the airplane was an Embraer 195.

Oh, I almost forgot! Totally uncharacteristic of Ushba – the entire 14 days of our action-packed expedition were characterized by EXCEPTIONAL weather. The same thing happened in 2004, when I, a “newbie,” descended Severnaya from Plateau along 4A with a night descent. Apparently, Ushba loves such peculiar guys and favors them. The “teapot” who visited Severnaya had never seen mountains before except Crimea and the Carpathians.

The Doctor, however, had climbed 3- and 4-grade mountaineering routes along the Caucasus passes: but this was his mountaineering debut!

Approach ridge.

After passing the micro-icefall of the Mazersky Glacier (2b – 3a category of difficulty), closely clinging to the Southwestern Ridge of Southern Ushba, walk along the ridge (snow, 1 category of difficulty) 100-120 m. Turn left, up the large-block moraine, hugging the simple rocks to the left for 200-250m (1a – 1b category of difficulty) to reach the tip of the ridge. Turn right, facing the “Pillar”, and, keeping to the tip of the ridge for 300-350m (2a – 3a category of difficulty) approach the first 40-meter rise of the ridge. Up a simple wide chimney (4a – 4b) for 10-12m, then simple (2-3 category) rocks for 12-15m, then left and up 15-20m of the same rocks you will lead to the top of the rise. 20-25m simple descent to the northeast, onto a flat snowfield. Here is an excellent bivouac. Then pass 100m of a simple horizontal ridge, approach the second rise. At the beginning, 30 meters of simple (4a-4c) cliffs, then the key point of the entire approach is an internal corner 10-12 meters (5b+ – 5c+, with pitons) – the middle of three visually identifiable cracks. Next, keeping to the left side of the ridge along rocks of moderate difficulty 76-90 meters (4a – 5a), reach a more gentle part of the ridge, along which, keeping as close as possible to the tip of the ridge (2b-3a category), approach the monolithic “Knife.” Along the left wall of the “Knife,” 20-25 meters of moderate climbing (5b – 5b+, there is a local fixed rope), leads to its tip, 50-70 cm wide. The “Cockscomb” ridge, 12-15 meters ahead, should be passed to the left and as high as possible. Then, straight ahead, 20-25 meters of easy (4b-4c) cliffs lead to the safest and most convenient site for a 3-4-person tent under the “Pillar.”

The 20-25 easy (4a-4c) cliffs end with a widening and flattening approach ridge. Approach the grotto at the base of the “Pillar” along simple inclined slabs (1 category) for 60-70m.

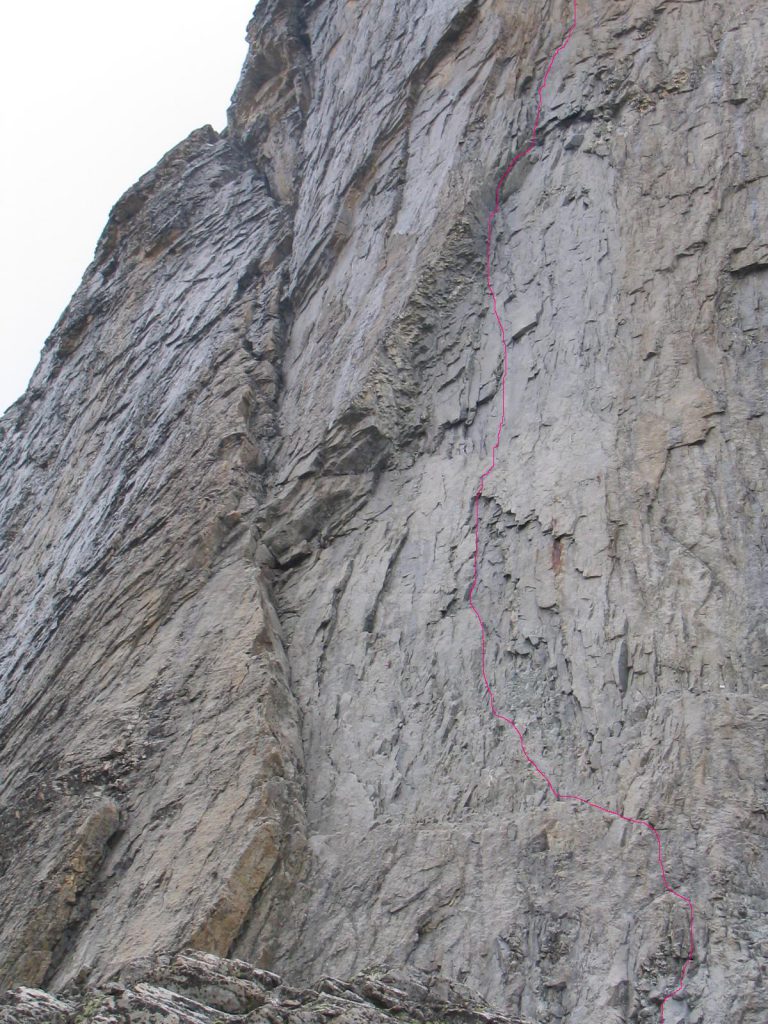

“Pillar”

Along the left edge of the grotto for 7-8m (5a-5b, pitons, small stoppers), then go 3-4m above the grotto to the right, then right and up 8-10m (5b-5c) to reach a ledge with a good steel bolt. From there, straight up along a smoothed slab for 7-8m (6a) to a breakaway (be careful, it’s loose). From the breakaway, left and up, there’s a simple (5b-5b+) exit to the ledge. There’s a station here. At 20-25m, we reach the Myshlyaev route; a system of wedged plates and blocks leads straight up to the “Chocolate Bar.” From the station, 7-8m of 5b+ – 5c+ (small and medium friends, medium and large stoppers) to the bolt. From there, traverse 3-4m up the slab to the left and up to a hook along a slab with indistinct relief (6c). Then, up along a system of indistinct spalls for 25-27m to a stop at a small, 50-70cm cornice (6a+ – 6b+, medium friends, medium and large stoppers, with a #2 camalot under the cornice).

After crossing the cornice (6a+), 5m of A2 (anchors) to the right along a smoothed slab, then 3m along widely spaced crimps (6c-6c+). A good ledge, station, two bolts. Slightly to the left and above the station is “Guillotine No. 1.” We first go around it along the rightmost crack (to the right of which is a smooth monolith) (5c+ – 6a, medium friends) for 6-7 meters to a bolt. From there, 8-10 A3 (first, four holes in a row for skyhooks, then 2-3 small stoppers, the choice of placement is limited) to the next bolt.

Then, up and left, A2 5 meters (or 7a-7a+) enter a large, smoothed inner corner. Follow this almost vertical route for 10-12 meters to a jammed block (6b-6c, small and medium stoppers), climb over the block (6c+, there is a firmly driven anchor just beyond the bend), then along a vertical, heavily smoothed corner for 10-12 meters to a bolt (6b+ – 6c, small and medium stoppers). Plus two medium friends just above the bolt – a hanging station.

To the right and up along a narrow, slightly overhangingThere’s a 3-4m (6c-6c+) chimney and an open chimney, then the chimney overhangs less and becomes wider. It goes 3-4m (6b+, with a strong but not fully inserted hook – requires a rope or harness) up and to the right. A 10-12m cascade of overhanging 2-3m corners, combined with 0.8-1m cornices (6b-6c, medium friends and stoppers), goes up and to the right, leading to a good ledge with two bolts. The belay is after a psychological half-rope, with the Big Central Cornice, “Guillotine No. 2,” remaining below us.

A system of blind cracks and corners leads upward, and we’re heading into the rightmost crack. 10-12m up and to the right (A2, small stoppers, or 6c+ – 7a) to the extreme (behind it to the right is a monolith) downward-facing cap. Along it, to the right, 3m A2 (small stoppers, better not to put pitons, possible 7a – 7a+), then 6-7m up to a bolt along a slab with good relief (6a+). Then 5-6m slightly up and to the left along a system of vertical cracks (6b-6b+, small friends and medium stoppers), then 5-6m things become easier (5c+ – 6a+). Along overhanging blind cracks, 4-5m A3 (anchors, small stoppers). Exit to a good, convenient ledge (there is a piton). From the ledge, to the left, up along a smooth overhanging slab A3 4m (anchors), immediately around the corner is a bolt. Then 8-10m along the smoothed vertical angle A2 (medium and large friends, possibly 7a-7a+) to a bolt with a knot jammed nearby in a crack. There’s a hanging belay here, and you can add a couple of medium-sized friends.

From the belay, first head slightly up and to the right along the vertical angle 8-10m A2 (larger than medium and large friends, possibly 7a-7a+), then along an 8-10m system of flakes (5c+ – 6a+, loops into rock eyes, medium friends) to the vertical Upper Chimney. If possible, without using bolts, climb 12-15m up the Chimney (6b+ – 6c, loops onto strong plugs in the Chimney, small stoppers). The hanging belay is on five old bolts gathered into a single loop, which should be reinforced with nuts nearby in the Chimney. Then a 5-7m traverse left and up an overhanging slab (very carefully load the bolts, choosing the best from the abundance. Otherwise, skyhook A3). On the outside, climb a large 3m leftward break (5c) and enter a large open corner. The corner is 32-35m, mostly 6a-6b. In 2-3 spots, carefully re-climb 2-3m on old bolts (if that doesn’t work, skyhook A2). Before turning left around the corner, there’s a hanging belay with two new steel bolts. Go left-up-around the corner, then, ignoring the old bolts, traverse left-up 37-40m (from 5b+ to 6b, small stoppers, hooks), turn right-up and (orienting yourself by the old bolts) 5-7m to a convenient ledge with 2 (one new) bolts.

From here, climb a heavily eroded, easy corner (the last 7-8m are 5c – 6a), keeping to the left of the tip of the buttress for 45-50m, then another 50-55m along the same corner, which has become more difficult (from 5c to 6b, medium and small stoppers, and some old pitons) to reach the summit of “Stolb.”

“Roof”

From the top of “Stolb” along a ridge of moderate difficulty for 100-120 m to a 50-meter gendarme, here turn right and, first, traverse 70-80 m along steep scree, then 40-50 m along 45* ice until you reach a steep rocky ridge. Next, 140-160m of mixed ice with 3-5m exposures of simple rock to the Schulze Ridge.

Along the ridge, 200-250m of moderate rock leads to the “Red Corner.” This leads 140-160m (from 6a to 6b+, ending with 5c-5c+, impossible to lose, very frequently broken) to a simple fore-crust ridge. Along this ridge, 300-350m of 2b-3a grade. Climb to the summit of Ushba Yuzhnaya.

We descended along the ascent route.

Recommended equipment: at least 50m ropes – 2, even better 100-110m “nine” (single rope), plenty of small stoppers, friends of all sizes (larger ones – on the approach to the Upper Kamin), sky hooks – 2 VD “Talon”, 2-3 anchors.

After the 1st, 2nd, and 3.5th ropes, sitting bivouacs for two people on rock ledges are possible. There is no water on the wall, only to the right of the “under-pillar” platform and at the top of the “Pillar.” The overall impression of the route’s difficulty is that it’s harder than the “Rhombuses” on Kant, easier than the “Center” on Morcheka.

Team:

Taras Pona – Self-Propelled Belay Unit, a barely visible but very powerful shadow of me, who “inspired” me to finally reach the Summit;

Valentin Skubak and Sergey Vasiliev – partial assistance with the drop-off, constant radio contact, and observation. And – praise be to them! – for catching our half-dead bodies on the descent, when all we could do was sit down and cry; and yours truly- Michel Voloshanovsky.

Author of the article: Michel Voloshanovsky

Source: alpinist.biz