The second highest mountain in the world is K2 (Chogori), the name of which is not associated with such a large and interesting history as Everest. Chogori was discovered by a European expedition led by Thomas Montgomery in 1856.

The mountain was designated “K2” as the second peak of the Karakoram. The summits designated K1, K3, K4 and K5 were later renamed and are now called Masherbrum, Broad Peak, Gasherbrum II and Gasherbrum I respectively.

However, when searching for the local name of Mount K2, it turned out that, despite its enormous height, it was nameless, probably due to its extreme remoteness from local groups.

However, before officially approving the name of the mountain as K2, researchers proposed to call it “Godwin-Austen” in honor of the famous British geologist and topographer, but this proposal was rejected by the Royal Geographical Society.

Later, travelers discovered local names, but there was no exact evidence that these names belonged specifically to Mount K2.

From The Chinese name of the mountain is Qogir, which eventually evolved into the name “Chogori” – Big Mountain.

Also registered names were: Lamba Pahar (“High Mountain”) – in the Urdu language; Dapsang and Kechu or Ketu in the Balti language.

And although K2 is only the second highest peak in the world, all climbers agree that it is the most technically difficult mountain.

The most difficult section is the “bottleneck” at 8400 meters, under the overhanging glacier, the passage of which is always “Russian roulette”.

Because of all the technical difficulties and the height of the mountain, K2 has always been an “obsession” for the world’s outstanding climbers.

In this article, we continue to consider the routes for climbing the world’s eight-thousanders, this time let’s take a look at the eight-thousander K2 (Chogori).

Recall that in 1939, an American expedition led by Fritz Wiessner climbed to 8400 meters for the first time in the history of mountaineering, stopping only 200 meters from the summit. This expedition was marred by a terrible tragedy: Dudley Wolf, Sherpas Pasang Kikuli, Pasang Kitar, and Pintso died in the assault camp.

So:

1902: Northeast Ridge. After five attempts, the British expedition of Oscar Eckenstein climbs to 6,525 meters.

1909: Southeast Ridge. The Italian expedition of Luigi Amedeo di Savoia-Aosta, an aristocrat and prince of Abruzzi, climbs to 6,250 meters. 45 years later, the first climbers from Italy, compatriots of the Prince of Abruzzi, reached the summit, climbing along this very ridge.

1938: Southeast Ridge. The American expedition led by Charles Houston reaches 8,000 meters.

1939: Southeast Ridge. The American expedition led by Fritz Wiessner reaches 8,400 meters for the first time in the history of mountaineering.

1953: Southeast Ridge. The American expedition of Charles S. Houston climbs to 7800 meters in 10 days.

Morphology of K2

Mount K2 has an almost pyramidal shape. The northern wall of the mountain is the steepest, rising above its base on the Kogir glacier to 3200 meters. On the other sides, the walls rise no more than 2800 meters.

On the northern wall there is a large buttress, which divides the wall into two parts: North-Eastern and North-Western.

The southern wall is the most pronounced mountain relief: on it, one of the ribs divides the wall into two parts; there are also at least three buttresses.

The eastern wall is characterized by a huge glacier, the largest on this mountain.

The West Face is clearly defined between two ridges: the Southwest and Northwest

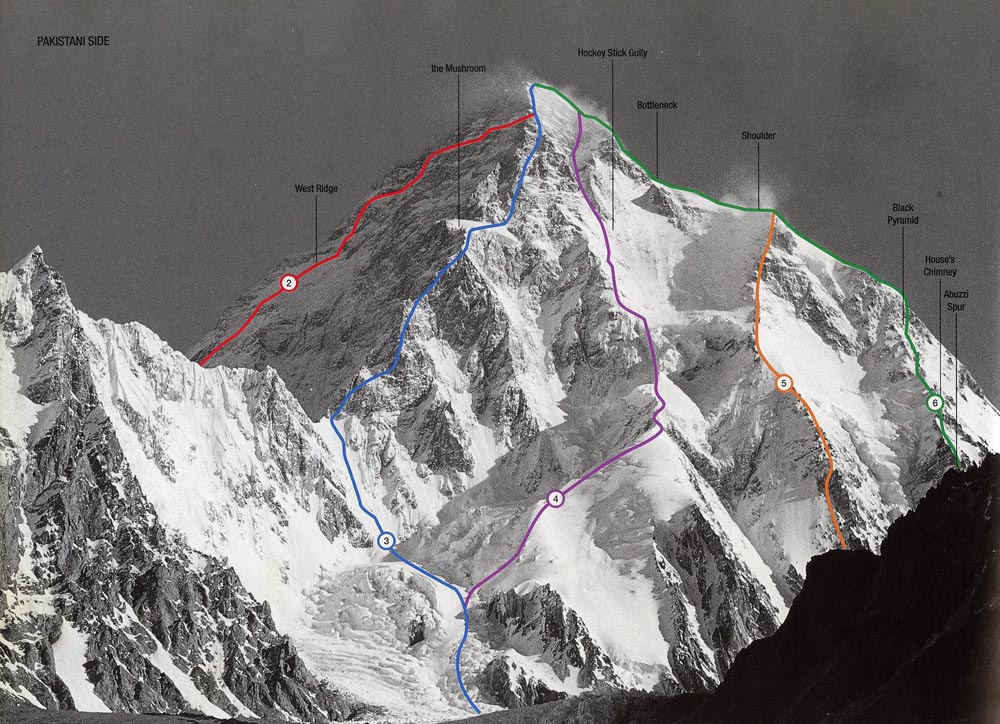

By now (2016), 9 routes have been established to the summit of K2, which mainly go along the edge of ridges, buttresses and crests.

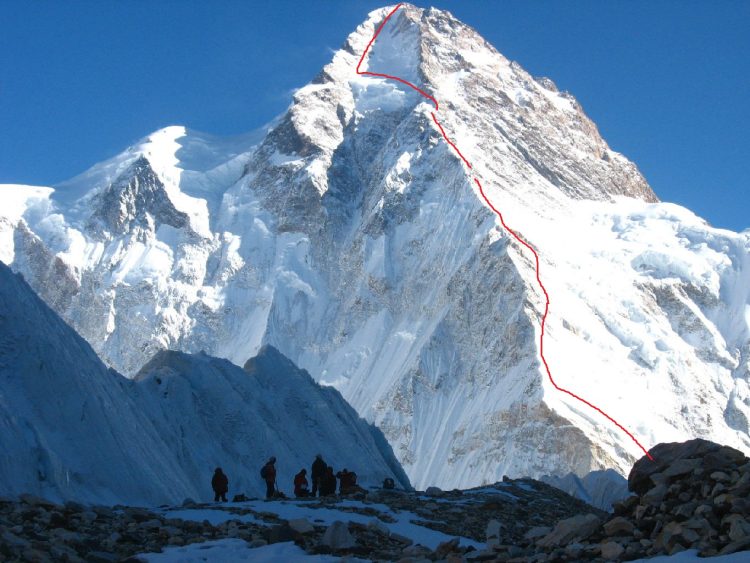

1954: Southeast Ridge (Abruzzi Ridge)

In 1954, a strong Italian expedition led by Ardito Desio came to K2.

Among the participants were scientists and eight professional alpine guides. Candidates for participation in the expedition underwent a very strict selection: a scrupulous medical examination andtraining camps in winter alpine camps. The expedition leader, 57-year-old Ardito Desio, a professor of geology, set certain conditions for the participants and obliged them to follow a diet, since “the ill health of one or more participants, caused by overeating or excessive alcohol consumption, could jeopardize all efforts.”

Each participant received an illustrated “K2 Guide” prepared by the expedition leader, so that they could all now prepare according to the theory. Apart from Desio, who had participated in the 1929 expedition to K2 organized by the Prince of Spoleto, cousin of Ludwig Amadeus of Sabatha, no one had yet been to the Himalayas.

In Italy, many doubted the significance of the expedition.

Already at the very beginning of the expedition, Mario Puchos, the alpine guide, died in Camp 2 from pulmonary edema. His body was lowered down and buried in a rock crevice next to Gilkey’s grave.

The Gilkey Memorial is a memorial sign that was built by Muhammad Ata Ullah and the team of the American expedition to K2 at the Base Camp of this eight-thousander in memory of their deceased comrade Arthur Gilkey – a member of the American expedition of 1953, who suffered from thrombophlebitis on the slope of K2 and eventually disappeared under mysterious circumstances.

“Not far from K2 Base Camp, an ideal place for the construction of the Memorial was found. It is separated from the Base Camp by a small distance, it is located just above it. In this place, the Godwin-Austen and Savoia glaciers run parallel to each other, separated only by a long, narrow strip of rock ridge.

This ridge juts out far from the main mountain mass, and therefore is illuminated by the sun’s rays throughout the day, allowing grass and flowers to grow in this small area surrounded by a vast desert of rocks, snow and ice. This “oasis” looks like a paradise in a sea of chaos. Initially, Muhammad Ata built a 3-meter-high stone pyramid, today this place is known as the Gilkey Memorial,” Ata wrote in his autobiography. Later, this Memorial became a monument to all the fallen climbers of the Baltoro Valley.”

The battle with the Abruzzo Rib lasted 8 weeks. Achille Compagnoni and Lino Lacedelli set up a tent in the last high camp at 8050 m.

Walter Bonatti and Hunza Mahdim climbed up to them to bring 19-kilogram oxygen cylinders needed for the assault on the summit. They failed to reach the high camp before dark and were forced to spend the night without a tent or sleeping bags. The night was stormy. The climbers did not touch the oxygen they had with them, knowing that it could ruin their chances of storming the summit. Hunza paid for that night with severe frostbite and amputation of fingers and toes. At dawn, they left the oxygen apparatus where they spent the night and began descent.

The next day, Compagnoni and Lacedelli found oxygen a few dozen meters below their camp. They took it and began to climb. Soon they reached the place where Weissner had sunbathed 15 years earlier. At 8400 they ran out of oxygen. They did not dare to leave the cylinders they no longer needed, and, loaded with heavy backpacks, reached the summit. It was July 31 at 6 pm.

They spent half an hour on the summit and left their oxygen tanks there. The descent was dramatic. Drinks laced with cognac relaxed them. Exhausted, they descended at night, poisoned by alcohol and lack of oxygen. They were extremely lucky when they fell from the upper edge of a crevasse that crossed a steep slope – they flew over the crevasse and landed on its other side. They lost their ice axes. Soon Compagnoni fell down along with a snow cornice and was stuck on the snow a dozen meters below. Lacedelli, also descending without an ice axe, also fell on the ice.

They descended to camp, where their friends were waiting. The next day, after leaving the camp, Compagnoni again flew 200 m on the ice slope. He again landed successfully in a snowdrift. They reached the base camp. The following message was sent: “Victory July 31, we are all together at the base camp. Professor Desio.” The names of the conquerors of the summit were not announced. Desio wanted to announce them upon returning to Italy.

After returning home, Compagnoni lost almost all of his frostbitten fingers. Lacedelli also lost several. The expedition ended in the courtroom.

Compagnoni filed a lawsuit against the Italian Alpine Club, which was the organizer of the expedition, hoping to somehow compensate for the damage caused by the amputation of his fingers and toes. Walter Bonatti, shocked by the official expedition report, which did not even mention his contribution to the expedition’s success, demanded an apology from the organizer. He received it 40 years later. The following year, he tried to find money for a new expedition to K2 to make a solo ascent using equipment abandoned on the slope. But the money could not be found.

Please note that in the modern ascent along this route, Camp IV is Camp VII in 1954. And, as you can see, the number of camps has decreased by 5!

1978: Northeast Ridge

This was the fifth American expedition, organized 40 years after the first. It was again led by James Whittaker. The climbers simply bypassed the difficult rock belt, climbing the Abruzzi Ridge by the easier route of the first ascentors. James Wickwire started using oxygen from 8100 m. 200 meters higher Lewis Reinhard also wanted to use oxygen, but was unable to.

Nevertheless, he decided to continue the ascent. On September 6, at 5-20 pm, they both reached the summit. Reinhard, the first climber to reach the summit of K2 without oxygen, began to descend faster, fearing oxygen deficiency. Wickwire lingered at the summit, changing the film in his movie camera. He began his descent as darkness fell. He had no headlamp. He spent the night 150 m below the summit, wrapped in a tent.

The next day, the other two climbed to the summit, also without supplemental oxygen. All four descended to base camp. Wickwire suffered several bouts of frostbite, pneumonia, and venous thrombosis. He was evacuated by an American military helicopter.

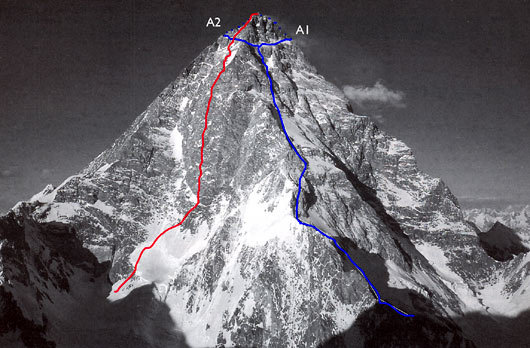

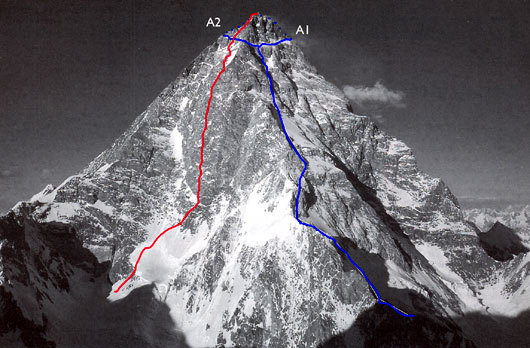

1981: West Ridge (some sources refer to it as the Southwest Ridge)

Japanese route via the Southwest Ridge, then a long traverse via the Southwest Face to the upper part of the Magic Line route.

First climbed by Nazir Sabir (Pakistan) and Eiho Ohtani (Japan) – they spent the night in a snow pit, using only a candle to keep warm, at 8470m.

Three years earlier, Chris Bonington’s expedition had abandoned an attempt on this route after an avalanche killed Nick Estcourt at 6,700.

Everest veteran Doug Scott was also caught in an avalanche, but his heavy pack saved him, acting as an anchor and stopping his fall.

This photo shows the West Face of K2 and the variations of the Japanese route, marked in blue: A1, the original route from 1981, and A2, a variation made by another Japanese expedition in 1997. Both of these lines have since been repeated by other expeditions. The 1981 route was repeated by an American-British team in 1993, who reached the summit without using oxygen tanks.

1982: Northern Ridge

First ascent from the North, from China. The expedition leader is Isao Shinkai. 7 participants reached the summit, all without supplemental oxygen. One climber died on the descent.

Note that, at that time, the approach to the eight-thousanders from China was a separate expedition, full of difficulties and hardships, they had to cross the deserts of Tibet with camel caravans.

Let’s clarify that this route is considered the third in terms of the number of successful ascents. Since its opening, 29 people have climbed to the top of the mountain along this line.

The following followed in the footsteps of the Japanese expedition of 1982:

1983: Japanese expedition. 4 people

1990: American expedition. 3 people

1994: Spanish expedition. 4 people, 1 died

1996: Polish expedition. 4 people

1996: Russian expedition. 3 people, 1 died

2007: Kazakhstan expedition. 2 people

2011: International expedition. 2 people

It is noteworthy that all successful ascents were made without the use of oxygen cylinders.

1986: South-Southwest Ridge (Magic Line)

This ridge, “thanks to” Reinhold Messner, is known today as the “Magic Line”.

Reinhold Messner, in 1979, while trying in vain to reach the summit of K2 via the Southwest Ridge (which he called the Magic Line) and the southern slope, said: “For the first time I encounter a mountain that cannot be climbed from any side.” In the end, he climbed to the summit, without oxygen, in semi-alpine style, following the path of the first ascentors – the Abruzzi Ridge. After returning home, he admitted that “Everest was a walk in the park compared to K2.”

The struggle continued. A French expedition led by Bernard Millet attempted to pass the Magic Line, it was the most expensive expedition in history,with a huge amount of equipment. 1400 porters carried 25 tons of equipment to the base camp. The expedition was accompanied by a 10-person film crew, photographers and journalists. A paraglider was raised to an altitude of 7500 m, and Jean-Marc Bovin descended on it to the base. After a long struggle, the French reached 8450 m. There were 160 left to the summit.

The magical line was completed by climbers from the Polish-Slovak team in the tragic year of 1986.

Anna Czerwinska, a witness to those events, summed them up in her book “The Horror of K2”: “I believe that we achieved a lot in terms of sport in 1986 on K2, we were terribly successful. But as members of the mountaineering community, we suffered great losses.”

That year there were 5 expeditions to the foot of K2. 27 climbers reached the summit, only four used oxygen. Seven died on the descent. In total, 13 people died.

Tragedies alternated with triumphs. After a heroic struggle, Wojciech Wroc, Premysław Piasecki and Peter Bozsik from the Czech Republic passed the Magic Line. They descended at night along the Abruzzi Ridge. In the darkness, Wroc suddenly fell from the end of the fixed ropes, which were not properly secured, and flew away.

That same year, the Italian Renato Casarotto attempted this route solo, but having reached the 8,300-meter mark, he was forced to turn back due to bad weather. Descending to the base camp, exhausted and tired, he, just 20 minutes away from his tent, fell into an ice crevasse and died in the arms of the climbers who pulled him out from blood loss and injuries sustained in the fall.

This route was repeated only in 2004 by a team of Basque climbers who were conducting their expedition in honor of the 50th anniversary of the first ascent of the mountain. Jordi Corominas reached the summit, but one climber died.

1986: South Face of K2

Following the route of the Polish-Slovak team, a significant event was the passage of a new route along the South Face by Tadeusz Piotrowski and Jerzy Kukuczka.

As you would expect from legendary climbers, they reached the summit without using oxygen tanks.

They descended the Abruzzi Ridge in fog, very windy and snowy weather without food or water for three days, spending the night without tents or sleeping bags. They descended on ropes while searching for the right route. Eventually they saw the tents of the Korean camp. They were descending a steep ice slope.

“I advised Tadek to go a little to the left,” Kukučka wrote in “The Ascent” – “Soon I noticed that he had lost his crampon. I asked him to be careful, but he made a sudden movement, and his second crampon flew off. I heard him cry “Jurek!” and saw him falling down. I was standing right under him on the steep ice – he fell on me with all his weight, I barely stayed in place, but I could not help him. I only saw him disappear over the edge of the vertical slope.”

Kukučka arrived at the base camp. Piotrovsky’s search was unsuccessful.

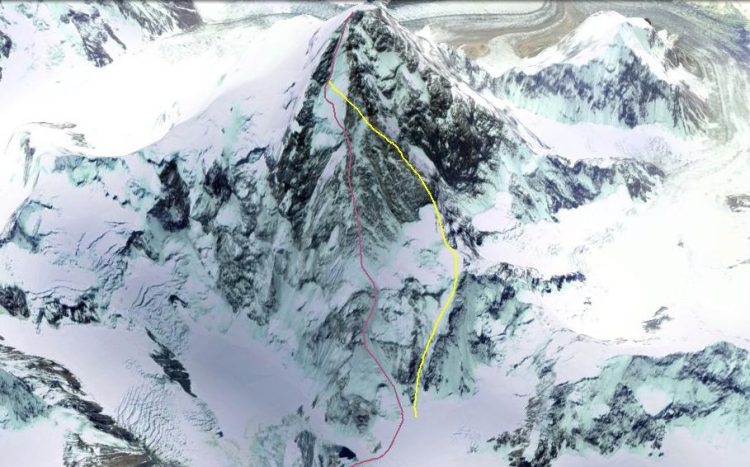

1990: Northwest Face – Northwest Ridge – North Face

Before this date, only 2 routes had been established from the north side: in 1978 and 1982. Now, for the third time, the Japanese have returned to the Chinese side of the mountain.

Their route began on the Northwest Face, transitioning at 800 meters to the Northwest Ridge, joining the 1982 route, and in the pre-summit part, transitioning to the North Face to the summit.

It is worth noting that a Polish expedition also attempted to climb this route, but their ascent was organized without obtaining permits from the Chinese government, and when the climbers were already at 8,200 meters, a message arrived at the team’s base camp that if the Poles did not immediately stop climbing, they would be sentenced to prison by the Chinese authorities.

Under threat of imprisonment, the Poles were forced to descend.

The Japanese team, led by Tomaji Ueki, having received the appropriate permission, using oxygen tanks and a hundred Sherpas in high-altitude camps, passed this route.

Two climbers reached the top of the mountain then. This line has not been repeated by any expedition so far.

1991: West Ridge – Northwest Face – Northwest Ridge

This route has much in common with previously created lines, but has a significant difference at the very beginning.

Frenchmen Pierre Beghin and Christophe Profit began the ascent along the West Ridge, crossed the Northwest Face diagonally, and reached the summit along the Northwest Ridge (the upper section of the 1982 Japanese route).

They climbed in alpine style, without using fixed ropes or pre-established high camps. However, the climbers used oxygen cylinders during the ascent.

The two climbers reached the summit. This route has not been repeated by anyone so far.

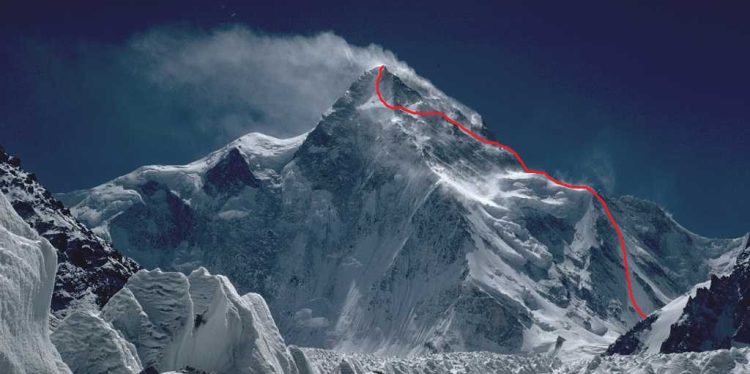

1994: South-Southeast Ridge (Cesen route)

The Americans first attempted this line in 1983, but they did not complete their project, stopping near the junction of the line with the standard route.

In 1986, Slovenian climber Tomo Cesen managed to connect the American line with the standard route, reaching this point in just 19 hours from base camp. However, his feat did not become the opening of the route, since Tomo was unable to climb to the summit itself, stopping at 7600 meters.

Only in 1994, a Spanish team went the full way from the base camp to the top of the mountain, stating that their line was even easier than the standard route.

The route was completed without the use of oxygen cylinders and is currently a popular alternative to the standard route and the second most climbed.

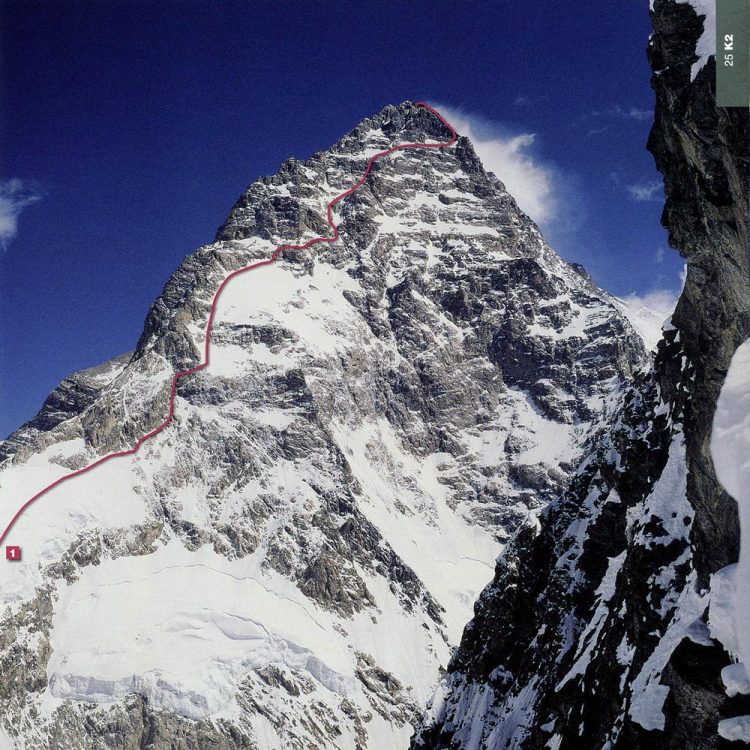

2007: K2 West Face

On August 22, 2007, a Russian team managed to overcome the previously insurmountable Chogori West Face. This extremely difficult ascent was accomplished without the use of supplemental oxygen. 11 climbers reached the summit.

The expedition then included:

Expedition leader: Viktor Kozlov

Team captain: Nikolay Totmyanin

Head coach: Nikolay Cherny

Viktor Pleskachevsky, Alexander Korobkov, Gennady Kirievsky, Evgeny Vinogradsky, Vitaly Ivanov, Gleb Sokolov, Vadim Popovich, Andrey Mariev, Sergey Penzov, Viktor Volodin, Valery Shamalo, Dmitry Komarov, Pavel Shabalin, Vladimir Kochurov, Igor Borisenko, Sergey Bychkovsky, Oleg Ushakov, Vladimir Kuptsov.

And the now deceased: Vitaly Gorelik, Ilyas Tukhvatullin, Alexey Bolotov

Eleven Russian climbers not only stormed the mountain, but made the first ascent without oxygen along the most dangerous and steep western wall.

Their route was so dangerous that the chances of success were minimal, and yet the well-coordinated work of the team, seasoned by the Soviet school of mountaineering, brought victory. This victory is recognized as a world record in high-altitude mountaineering.

The expedition took place from June 7 to August 24.

The following climbed to the summit:

August 21 – Andrey Mariev, Vadim Popovich,

August 22 – Pasha Shabalin, Ilyas Tukhvatullin, Vitya Volodin, Gesha Kirievsky, Vitalik Gorelik, Zhenya Vinogradsky, Gleb Sokolov, Kolya Totmyanin, Lesha Bolotov.

RESULT

Above we described 10 routes laid to the summit of K2 (from 1954 to 2016), some climbers note not 10 but 9 routes on K2 (combining the lines of 1990 and 1991 into one route).

Moreover, we note that there is a wall on K2 with only one completed route, as you have certainly guessed, we are talking about the Western Face and the Russian route of 2007.

Let’s present all these routes in a table, noting the year of creation, whether this route was passed for the first time using oxygen cylinders, whether it was repeated later and how many people have reached the summit via this route.

| Route | Year | First ascent with O2 | Repeat | No. of climbers |

| Southeast Rib (Abruzzi Rib) | 1954 | Yes | Yes | More than 200 |

| Northeast Rib | 1978 | No | No | 4 |

| West Rib | 1981 | Yes | Yes | 4 |

| North Ridge | 1982 | No | Yes | 29 |

| South-Southwest Ridge (Magic Line) | 1986 | No | Yes | 4 |

| South Face | 1986 | No | No | 2 |

| Northwest Face – Northwest Ridge – North Face | 1990 | Yes | No | 2 |

| West Ridge – Northwest Face – Northwest Ridge | 1991 | No | No | 2 |

| South-Southeast Ridge (Cesen route) | 1994 | No | Yes | more than 50 |

| West Face | 2007 | No | No | more than 9 |

FUTURE ROUTES ON K2

As we know, the Polish route of 1986 is considered the most dangerous on K2 due to the constant high risk of avalanches, and the West Face is very difficult in technical terms.

Therefore, the primary task of climbers of future generations will be to repeat these lines in pure alpine style (without the help of Sherpas, oxygen cylinders and pre-installed and installed ropes and camps).

In 1991, a French expedition came as close as possible to passing the line in alpine style, however, the French did hang ropes at the bottom of the route.

The second task for the climbers is much more difficult: this is the first winter ascent in history.

The East Face of K2 – still unconquered

On the eastern side of the mountainsy, between the two routes of 1954 and 1981, not a single expedition even tried to climb the wall: three buttresses or ribs are clearly visible on it, along which one can climb to a small glacial plateau, from where a flatter and easier part of the route goes to the summit.

The problem is that due to longer exposure to the sun, the glaciers on the eastern wall are very unstable and prone to collapses. Even the smallest fragment, falling from 7000-8000 meters, can cause great harm to a climber climbing from below.

But, as experienced climbers say: there are no impossible peaks and routes. In general, the East Face is possible to climb if you manage to climb the most difficult part of the route in one night, and are lucky with safety in the pre-summit zone.

The southwest wall of K2 is also still unconquered

This wall has also remained without any attempts to climb. Compared to the East wall, it has a significantly lower risk of avalanches, but much higher rock and technical difficulties.

However, taking into account that the center of the almost identical Western Wall was climbed in 2007, the neighboring Southwestern Wall may also be climbed in the near future.

Other possible routes on K2:

The mountain has ridges along which the routes have not been fully laid: the North-East, East, North and North-West ridges are awaiting full ascents.

All the climbs that have been made on them turned onto the walls at the top, rather than continuing along the ridges.

In conclusion, we note that according to K2 statistics, exactly 300 people climbed this peak from 1954 to 2009. During the same period, 77 people died on the mountain.

The material was taken from the site: https://4sport.ua